When the boys were still tiny, we moved from the pine tree-lined streets of a small town in Central Oregon to a slowly decaying, dusty neighborhood in an even smaller town in Southern California.

Instead of pine trees, we would sit under orange trees and talk about avocado ranches.

That was a strange thing to hear.

Avocado ranch.

As a child raised in an eastern farming community in Montana, a ranch most definitely meant tall, lean men in cowboy hats riding short, powerful horses while weaving past horns and hooves in arenas and feedlots.

That was ranching.

Wrestling calves to the ground, white teeth flashing in dirt-streaked faces, calls and whistles directing speckled dogs in the clean country air. The massive bodies of beef cattle flowed around them in a primal, dangerous dance.

Branding fire smoke would have added to the haze of dust, and the acrid smell of sweat would cling to us as we hustled toward the house, following the clang of an iron triangle calling everyone to tables loaded with food. Every sense amplified by a purpose that bound us together in a singular lifestyle built through generations.

That was ranching.

To me.

Of course, I’m sure that’s exactly how the gentlemen ranchers in California felt. Tapping into the raw masculinity of quad-runners, baseball caps, designer sunglasses, and fruit salvaged from the leaf-covered dirt floor of the orchards, narrowly rescuing their harvest from squirrels and the dogs who roamed nearby.

As you can imagine, I never could say “avocado ranch” with a straight face.

We’d moved into the back two bedrooms of Brian’s grandfather’s house, planning to only stay a little while.

In our hearts, we longed to return to the pristine beauty of the Pacific Northwest. But when his health took a downward turn, we were told he needed support.

So, we stayed.

Not just because we had the flexibility, but because family loyalty seemed like it chose for us. It hung over us like a choice we couldn't ignore.

Brian went to work with his friend, Arnie, in sunlight-filled avocado orchards, while I stayed home and cared for two little boys and an old man loaded with time and stories. The days piled onto each other as he began to disappear into a dementia we didn’t see coming.

During the day, we had Matlock reruns at 10 and Walker, Texas Ranger at noon. The pop culture of an older era blared through the speakers as the television filled quiet hours. Most often we sat in companionable silence, but sometimes we talked.

He told me about his own childhood as the red-haired, freckle faced son of a bona fide Cherokee Princess in the Dust Bowl of Oklahoma. Portrayed as angry and vengeful, she was a woman whose neglect and anger still scarred him nearly 7 decades later. Her tribal identity used to gloss over the cruelty she showed him, as if that were enough to excuse the lack of love.

That was the only legacy he ever shared of her.

Proud of the stand he took against the racism that surrounded him, he told me how, at his bicycle shop, he hired men freely—while the world outside still clung to white-only drinking fountains like they were law.

Which, I suppose, they were. As horrible as that is to think about now.

Comforted by the familiarity in his words, my mind would fill with memories of the farm and the animals, planting and harvesting, and the trustworthiness of the cyclical hum of seasons. I imagined the throbbing drums of the Pow Wow and craved the sense of belonging that tribal traditions create.

Sometimes we’d laugh at the similarities in our lives as I’d tell him about my backward, country upbringing, and there was, for me, a sort of unspoken camaraderie in the recognition that neither of us knew the gentleness of a mother’s love.

As the disease slowly ate away at his sense of self, his freedom to engage with the world shrank. Embittered, he withdrew into himself.

Still, for several months, I would spend hours learning my husband’s family history while the afternoon sunlight filtered into a living room last updated in the late 70’s. The little boys played on the floor, I’d curl up on the cream sofa, and he’d stretch out in his pleather recliner. While dinner simmered on the stove and words flowed between us, decades of life would fill the spaces that dementia was slowly taking away.

Occasionally, he’d go out to lunch with a friend, or Brian’s parents would pick him up, and on one such afternoon, he was gone.

The boys slept the hour away, and I was chapters deep into a book when sharp knocks at the door surprised me.

Our neighborhood was predominantly Mexican, with families drifting between California and Mexico. Spanish echoed down the potholed street more often than English, rising above mariachi music and the rev of engines.

It wasn’t a dangerous neighborhood, exactly, but we, as the lone white family on the block, were an obvious misfit. Even though Brian’s grandfather had lived in that home and raised his own family there long before the demographic changed.

So, when I opened it to see two white girls in skirts, I was startled, to say the least.

I took in their modest appearance. The name badge on their chests and the silver-edged, navy-blue book in their hands easily giving them away.

Quickly, I invited them in.

I’d walked a few miles in their casual, low-heeled shoes. I’d felt the awkwardness of standing in front of strangers, eternity forced into your language, and the bittersweet hint of martyrdom that lingers in repeated doorstep rejections. Perhaps it was that sense of solidarity that drew me to them, more than any kind of oppositional evangelistic temptation to argue theology and prophets.

Our conversation unfolded comfortably as we shared our lives. Stories of faith and miracles, ministry, and purpose were met with nods and smiles. I shared my spiritual awakening, and they nodded along, bright-eyed and eager, as the moments flew by.

Our vocabulary intersected at so many points that it was like we finished each other’s thoughts.

After a while, I offered them iced tea and we prayed together, each of us invoking peace and blessings, wisdom and goodness on the other. I prayed to the God I knew in my heart, and I am sure they prayed to the God they knew as well.

As they walked away, I said a few more prayers for their safety and well-being. It seemed foolish to send young girls to navigate streets edged by machismo and the wandering eyes and leering voices of the men who stood next to their cinder-block fences.

We never talked about where we were from, but fresh-faced country girls—raised on handshakes and pickup trucks that smell like hay and wet dogs—are easy to spot.

Especially when they look like you.

I’ve wondered, through the years, what could drive naive young women to engage in risky and even dangerous behavior in the name of God and church, but I know the mission before them may have felt like it was rising stark, imposing, and impossible to refuse. Our leaders give us goals, and we can either accept them, pleasing God, or reject them, and risk the safety of our souls.

In a world where it’s hard to find objective truth amid a cacophony of noise and contradiction, there’s a comfort in a kind of faith that offers simple choices—right or wrong, in or out, saved or lost.

Obedient or rebellious.

For many, decisions are made after a clear evaluation of the branching pathways that diverge from the main timeline of their lives.

Perhaps a seemingly small choice, abandoning the drama club and, instead, joining the business club becomes what redirects a teenager from a future filled with poetry and prose to one structured by mergers, metal, and corner offices.

In place of velvet-covered seats and tiered auditoriums, life could unfold in rooms lit by fluorescent bulbs, lined with screens and business suits.

Some might see it as a loss. But the sharp clarity of bullet points, the precision of contract negotiations, the quiet power of a closed-door boardroom tease at a possibility that thrills and whispers promises of an unexpected passion.

An unexpected passion that stood toe to toe against the conventional paths of acceptable women’s roles. A possibility that died in its infancy when forced to exist behind less objectionable choices disguised as better ones.

The right ones.

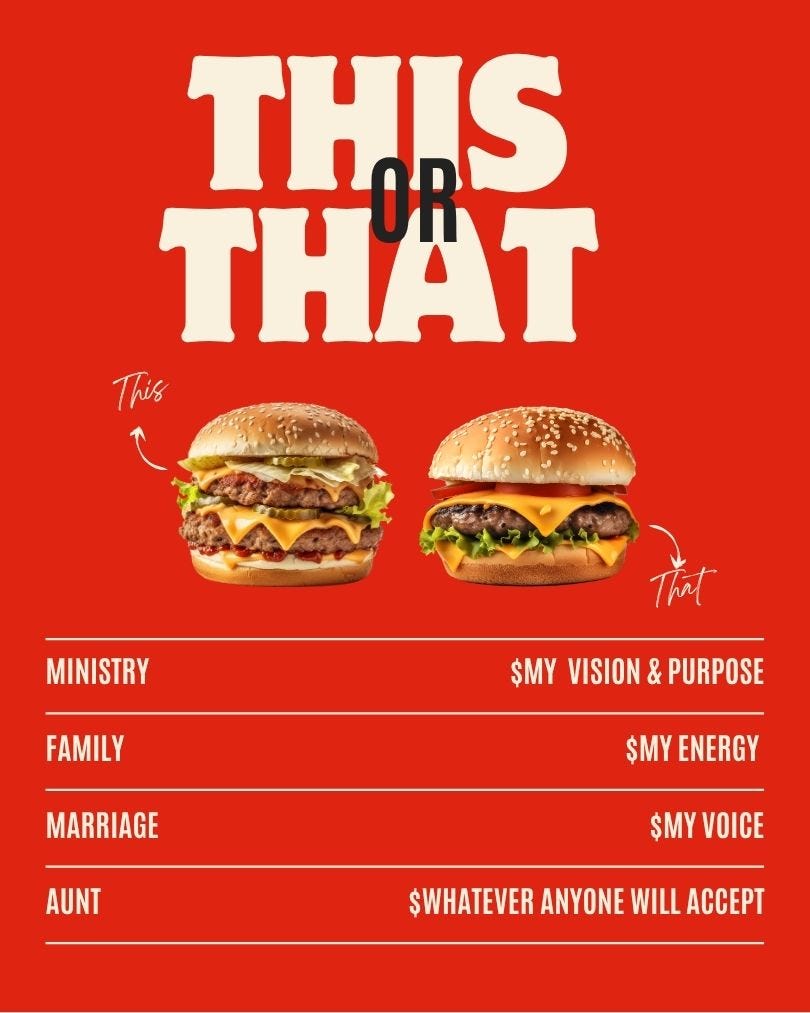

There is an assumption, easily made, that the decisions people make come from a place of understanding the world the way you do. Sitting next to someone at a restaurant, it’s easy to think they ordered a cheeseburger after reading and considering the whole menu. But maybe they didn’t choose the cheeseburger because they wanted to.

Maybe they couldn’t read.

Reminded of the skewed logic of that world, of dreams stifled by obligation and words crammed tightly into sentences that I didn’t craft, the conversation on a recent podcast felt very familiar.

For over an hour, the host and his guest examined books written to conservative Christian women by Conservative Christian women. Books and stories painstakingly curated to provoke better and more compliant versions of themselves.

I sat and listened as these outsiders to a world I knew intimately wrestled with a familiar brand of ideas. They shared keen insight and openness as they acknowledged their own confusion while trying to understand why women, with opportunity and enough intelligence to create and promote their own written works, would still not only choose but also promote this lifestyle.

It seems impossible that women would fight for a lifestyle that seemed to exist as a means to keep women compressed into forms that deny their own autonomy.

If you haven’t lived in this world, this is something that you might not understand.

Within the acceptable conservative and traditional women’s roles endorsed by powerful men in closed religious circles, there are imperatives and requirements. Lists of unspoken dos and don'ts are often framed by harsh penalties for failure. A strong connection forms between those rules and the belief that anyone who fails to fall into their overly simplistic viewpoint is not trustworthy.

Essentially, How to Build a Cult 101.

Slowly, I am learning that outside that world, there are people who see a field of options, vast and impossible. A world where life is made of a nearly universal understanding and expectation of choice. A fundamental belief that life is made of what you are drawn to and what you have drawn to yourself.

Within that belief lies an expectation that you, as an acceptably intelligent person, will reasonably and thoughtfully select a path to build a life made in the shape of yourself.

From that perspective, it is not surprising that some assume that conservative Christian women are doing the same. It follows, according to that logic, that they have embraced these roles because they consciously and intentionally chose that narrow path.

The correct conclusion seems to be that, though recognizing a sea of options, some have intentionally settled on subjugation.

And perhaps, for some, that is true. But, for many conservative Christian women, when faced with their options, they simply chose to survive.

Try to remember that the next time you wonder why they stay and why so many women still rigorously defend this position.

As all those pieces of the puzzle lined up and began to snap together, I looked back at that afternoon in California and revisited the breathtaking innocence in the faces that had stood in front of me.

Maybe that’s why I opened the door without hesitation. Because I recognized them—not just who they were, but who I had been, and I had a glimmer of where I was headed.

Today, writing here, I wonder who I might be becoming.

One choice at a time.

So clear and yet so completely opaque.